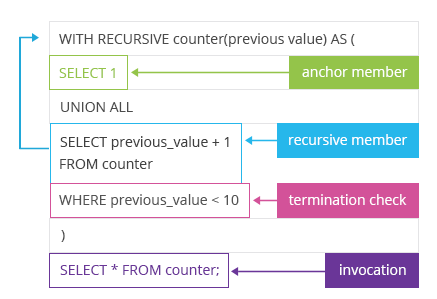

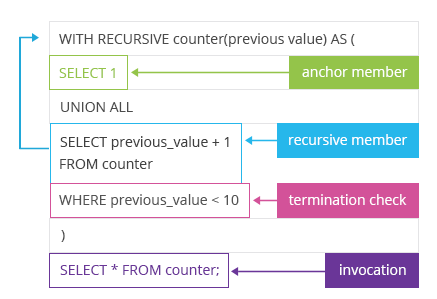

Now, let's discuss the remaining parts of our example query. We'll paste it here again for your convenience:

First of all, note that we used UNION ALL to join the anchor member (SELECT 1) with all further recursive steps (SELECT previous_value + 1). Instead of UNION ALL, we could also use UNION, which will remove duplicate values from the recursion. In our case, no duplicate values exist, so there is no difference between UNION and UNION ALL.

Once the recursive CTE is completed and our temporary table is created, we need to query this table to actually see any results. That's why we put

SELECT *

FROM counter

outside the CTE. This part of the query is called invocation.

The animation below shows how our final recursive table is constructed.

Restart animation

Technically speaking, recursive CTEs do not use recursion, but iterations. Still, as the SQL keyword for this kind of queries is RECURSIVE, it is common to call such queries recursion. Treat it as some sort of convention rather than a technically accurate description.